The Conference: Remembering, forgetting and moving on

Posted by Dr Janet Harris

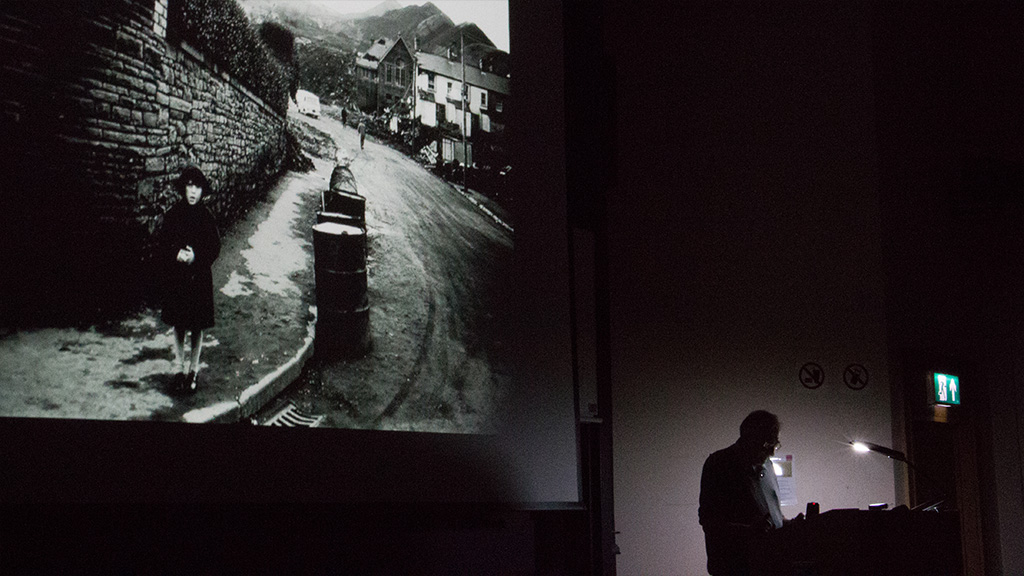

The conference began with a story of a child. Standing in front of a picture of the white-haired 8 year old boy, an adult Jeff Edwards and ex Merthyr Tydfil council leader told his story of that day.

He was last survivor to be rescued from coal tip no. 7 which slid down the mountain nearly 50 years ago engulfing Pantglas junior school in Aberfan on October 21st 1966. 144 people died, 116 of them were children.

Organised by the School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, the structure echoed that of a broadcast programme, starting with an authentic emotional tale to hook the audience and set the context for the day. Among the invited speakers and attendees were Aberfan residents, and participants from the media and academia, gathered to examine how both the media and the community remembered, and forgot, and whether and how both groups have or could move on.

What emerged was a moving and fascinating day where some of the disaster survivors: children, family members, reporters and emergency service workers, spoke publicly for the first time after 50 years, where the ‘academic’ conference was transformed into something else. It moved beyond the didactic and performative to become a safe location where people could speak out and exchange and share knowledge both within and beyond the institution.

The power of many stories lay in their recollection of ordinary details; Jeff Edwards talked about being buried by the coal, but noticing the twinkling of the particles of dust reflected in the light; Former BBC News Editor, Elwyn Evans talked about the shame he felt when he stood for 8 hours watching events on the 21st October, not knowing what to do and unable to do anything. These stories of humanity encouraged others to speak out. Yvonne Price, a police officer, spoke of being made a mortuary assistant and being kept drunk so she could do the job.

The photojournalist I.C. Rapoport, who photographed Aberfan for Life immediately after the disaster, also talked about his stay in Aberfan, telling the stories of the people in the photographs, and how he came to take them. His emotion at the memories and the power of the photos enmeshed the audience in the story. Sontag writes of a picture; ‘There is the surface. Now think—or rather feel, intuit—what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way’ (1977:17).

The occasion of the conference also contributed to the speaking out, where stories told are part of the ritual of remembrance. What we were examining was not just how the information of the event was distributed to the world, but also how the memories of the event were shaped by the journalism of many of the people at the conference; where the media coverage constructed by journalists, photographers and documentary makers entered into the collective memory of the event. People wanted to share in the ritual of remembrance, but also to add to, and dispute the collective memory with their individual memories.

The anger at media coverage and at the appropriation of the story for commerce or for entertainment also bound people and encouraged some to ask whether the media intrusion should stop. Chris Morris who had made a documentary ‘An American in Aberfan’ to mark the 40th Anniversary said there were 17 different production companies looking for stories when he made his film. Gaynor Madgwick, a survivor and author of ‘Aberfan, Struggling out of the darkness: A Survivor’s story’, argued that there is a place for the media to keep the story alive, it should not be forgotten, but that it has to be remembered appropriately. The community has moved on physically, she added, but not mentally or emotionally. There are so many constant reminders that it is impossible to forget the past.

Another survivor who spoke for the first time emailed after the conference saying that he did not expect to speak ‘however the right conditions were created and a safe space emerged allowing me and others to talk for the first time’.

The safe confines of the University enabled people to speak freely amongst people who shared their experiences and knowledge; they were not judged, and were not exchanging information for commerce or entertainment. They were able to remember, to listen to others who had gathered together to share information, to know that their story would not be forgotten, and to discuss ways to move on.

The conference ended with the story of children. The broadcaster Vincent Kane who had reported on the disaster gave a searing condemnation of the national Coal Board, the Union of Mineworkers and the media, but he finished with the tale of the Pied Piper of Hamlin, where the children were promised a joyous land and led into the mountainside, never to be seen again.

Sontag, S (1977) On Photography. New York, London: Anchor Books