The game design industry offers plenty of opportunities to exercise innovative flair. How can you cash in on this lucrative enterprise?

You have some visitors and dinner is taking a little longer than expected. It’s time to entertain your guests for 20 minutes, but what would keep them occupied?

Then, the penny drops. There’s a game of Connect 4 collecting dust in a cabinet next to the armchair. The dinner party has been saved from eternal doom.

Most people have seen a board game. Monopoly, Snakes and Ladders, Chess and Scrabble are just a few classics that have become household names. Monopoly alone has torn many a family apart. Board games have afforded players a few minutes of fun or several hours of entertainment for centuries. So what does it take to switch gears and take up a position behind the scenes as a game designer?

Adam Porter is a lecturer and dentist from Oxford who designs games as a hobby: “I usually manage to find a day in the week where I’m designing games. One day a week I’ll sit down and spend that time designing.”

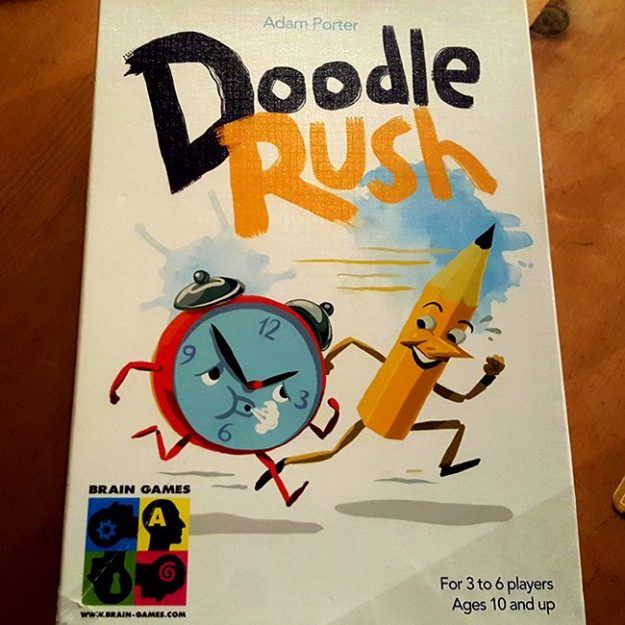

Porter has three games that have been released in countries like the US and Germany.

Porter became interested in game design after being fascinated with the mechanics multiplayer tabletop games: “I played lots of games and wanted to get behind the curtain and behind the scenes and know how things are working. I always tend to go that way, I wanted to see how these games are made and see if I could do it too.”

He is the co-ordinator of a group called “Playtest” which is made up of game designers who meet weekly in Cardiff. Their gatherings involve testing original board games designed in their spare time.

“Play testing is a term within the board game industry. It’s the most important bit of game design, it’s test test test test your design… Playtest Cardiff is part of a wide network of groups that are play testing around the UK,” says Porter.

The UK Playtest network is internationally renowned for bringing talented game designers to the fore. Cardiff Playtest has been running for four years.

Some games require strategic thinking while others are won based on good fortune.

Robert Fisher, a game designer from Penarth says: “There’s been a change in the types of games designers want to create. There is competitive play where players battle against each other to win a reward or fulfil an objective.

“Then the newer style is called the co-operative game, where the players work together to achieve something. It could be killing a boss or saving a town. The challenge for designers is that sometimes there is a bossy person who wants to take control of the game…or there are quieter players who don’t make any of the strategic decisions. Designers need to make sure there is a balance and that everyone starts on equal footing.”

A time-consuming hobby, game design requires a combination of skills: “You have to be a problem solver, a creative person, imaginative,” says Porter.

“There’s two different approaches to designing games, you can try and design games based on creating the universe and the story first and then trying to make the rules of the game. Those are for the people who like building worlds. Then there’s the gameplay method, where you make the rules first and then imagine what that story might be later on.”

Porter takes a scientific, mathematical, puzzle-based approach to game design.

“Either way works and most often, we’re doing a combination of the two.”

The challenges of game design span the process from devising a concept to the creation of rules and production of materials.

“It can be anything. The initial challenges are coming up with ideas. I don’t have a huge problem with that – ideas come to me fairly freely. That’s not the same for everybody, lots of people struggle at that point, but I frequently find that an idea works in my head and then I put it on the table and it doesn’t work at all…so then it’s a case of testing it, testing it until trying to fix that problem.”

“But sometimes you can’t even tell what the problem is. All you know is that the game isn’t fun, and that’s the most challenging bit,” says Porter.

“It’s a constant discovery process, I am very happy with the way it’s gone, you’re constantly learning.”

Porter is influenced by other board games: “I play a lot of board games and we’re at a golden age where well over a thousand games will be released each year.

“I know which sort of games I want to play and which designers I want to follow and I’ll play their games and I find them constantly inspiring.

“When someone comes up with something totally new that I’ve never seen before, that’s what I look for with my own designs. That’s where I get my inspiration.”

Porter says that this hobby is inexpensive: “Our group is happy to test games that are just on scraps of paper with pencil, biro and some very basic components.”

“Once you get to the point where you’re trying to produce something really polished that you can send to publishers… then it gets a little bit more expensive but even at that point, all they’re expecting to see is some printed stuff on card.”

Be warned, however, that game design may just take over your life: “I don’t have time for hobbies outside of [game design]… it’s so all-consuming because if I’m not designing games then I’m playing them. I used to have other hobbies. They’ve kind of fallen by the wayside a bit.”

So now you’ve read this article and feel that you have found your calling as a game designer. The creative process of inventing a board game can be divided into three distinct stages.

Stage 1 – Coming up with ideas

- Play existing games for inspiration and think about how you would improve them.

- Choose an appropriate age range for your game and decide how many players it is suitable for.

- Decide whether participants are competing against each other or working together to accomplish a goal.

- Think of what players need to do to win.

- Consider game mechanics (How the game will work. Will players roll a dice or draw cards?)

- Think of a thematic genre for the game, such as science fiction, adventure story or murder mystery.

- Make a draft list of rules.

Stage 2 – Making and testing a prototype

- Sketch a rough draft of your board (Will your game follow a path? Will it have a finish line or a playing field?).

- Put together game pieces (Items like buttons, poker chips can be used as placeholders).

- Test your prototype alone, and be critical.

- Test your game with friends and family, explaining the rules.

- Test your game with strangers and make adjustments to the rules.

- Make a final list of materials you will need to make your final game.

Stage 3 – Manufacturing, producing and distributing your game

This process is called publishing, and there are two main routes: self-publishing and pitching your idea to a company.

Self-publishing is a large financial investment and more information on this can be found here:

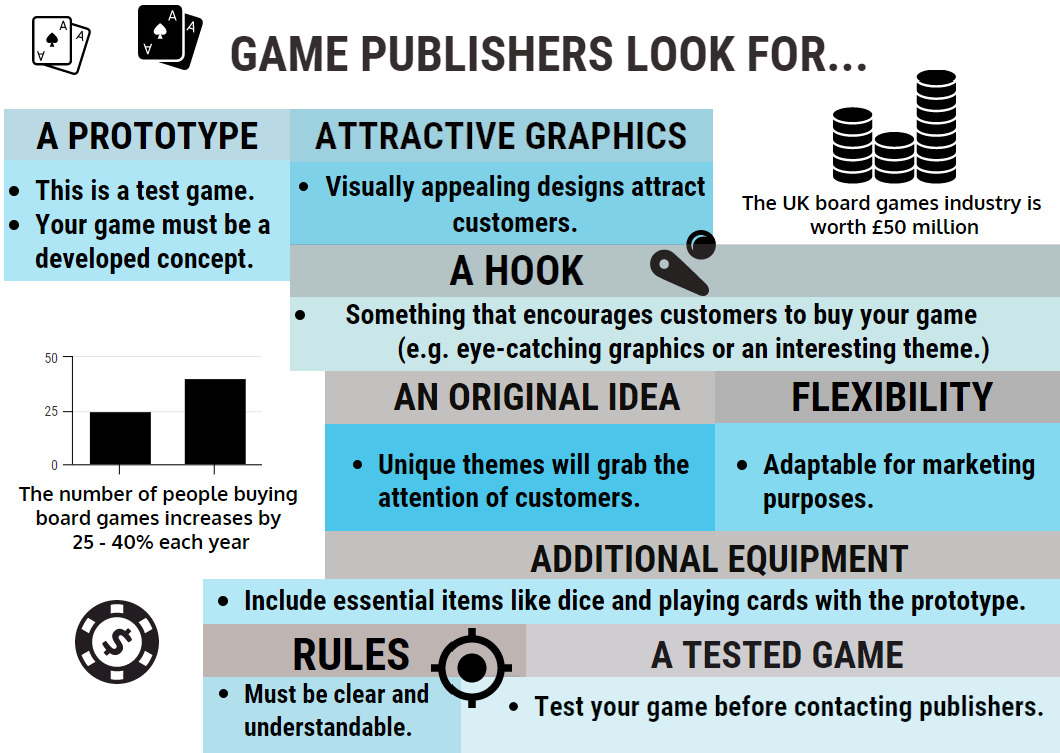

The more common route is sending your prototype to a publisher who can help you develop and sell your game. Game proposals are frequently rejected, so it is essential to make sure that your pitch is airtight.

Here are some things to consider before sending off a proposal:

Additionally, you should check that the publisher you have in mind is still accepting submissions and that they publish games in the same or similar genre as your prototype.

Happy designing!

Sources:

http://www.amherstlodge.com/games/reference/gameinvented.htm

Duffy, O. for The Guardian. 25.11.2014. “Board games’ golden age: sociable, brilliant and driven by the internet”. The Guardian