Other voices in Wales speak about socially inclusive theatre:

“When National Theatre Wales was set up we made ‘community’ a core value i.e. it’s part of everyone’s role. It means we can build long term relationships over time and have worked with a range of communities and people, many of whom may fall into the category of ‘hard to reach’.”

- Devinda De Silva, Head of collaboration, National Theatre Wales

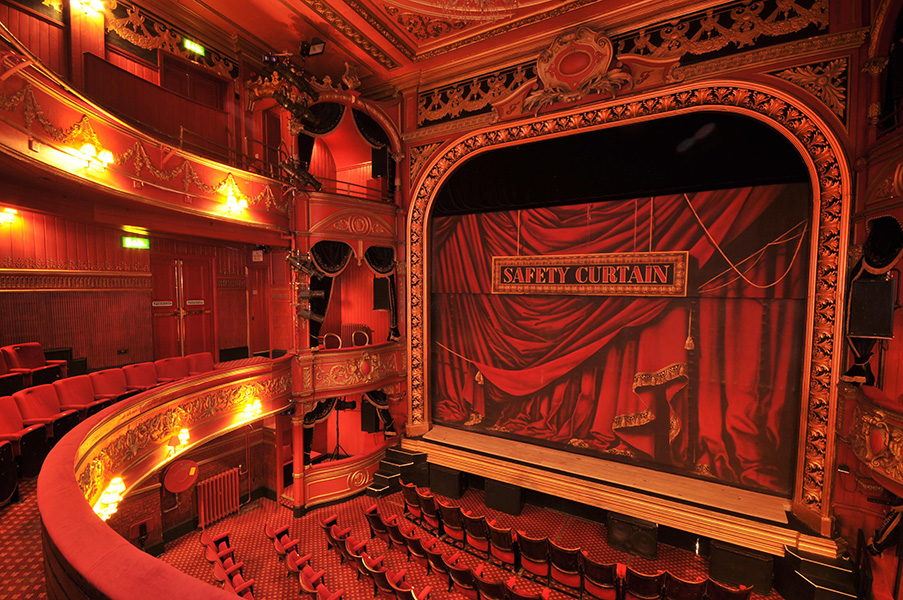

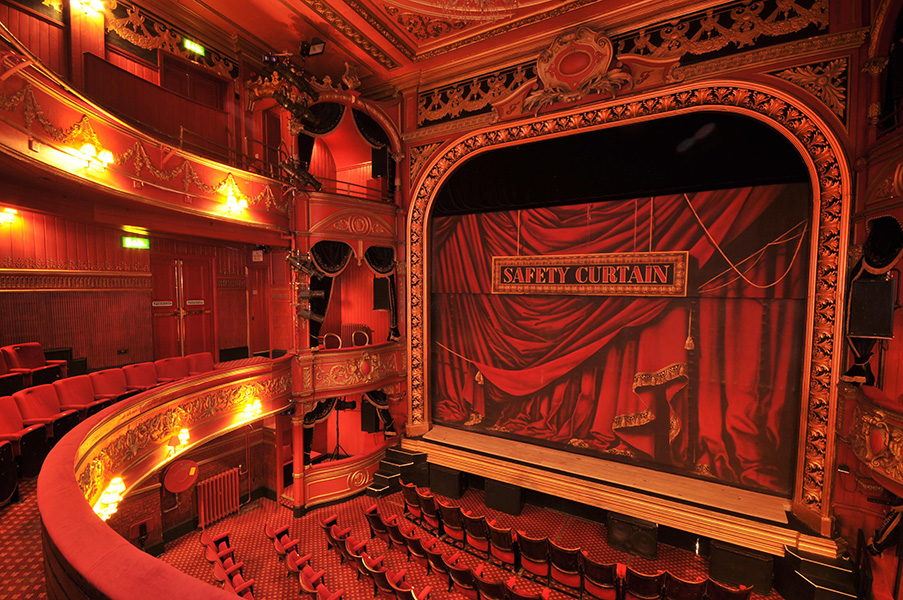

People often perceive theatre as grandiose, but theatre companies are trying to change that (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

“The council is committed to theatre and the arts in the city and especially that its cultural offer is accessible and of relevance to all of its citizens. The Council’s Cultural Projects Scheme (CPS) has supported a number of small community arts projects. These projects provide match funding to grassroots arts activity that has a transformational impact on participants’ lives.”

- Councillor Peter Bradbury, Cardiff Council, Cabinet Member for Culture and Leisure

We’re Still Here by Commonwealth Theatre challenged perceptions of what theatre looked like (Photo credit: Jon Poutney)

“I see more and more small theatre companies trying to put on innovative work which I think is great. However mainstream theatre to me does still very much cater for the few. By going into schools, we hope to use the creative arts in order to include those who are usually excluded from the theatre scene, and in this way challenge perceptions of theatre and what art can be.”

- Michael Barnes, Educator and Actor at Going Public Theatre, a charity formed in 1990 that focuses on theatre in education

Cardiff-based Eno Theatre recently showcased “Writing to Reach You,” a performance about mental health (photo credit: Nerida Rose Bradley)

“Theatre is usually grandiose, white buildings inaccessible to most people. A big problem with theatre in Cardiff at the minute is that it’s very very very white. There’s a huge problem with BME talent not being recognised within Wales.”

- Danny Muir, Freelance Producer, Eno Theatre

“Working class” and “theatre” aren’t often paired. But are artists able to break through the class ceiling and create work that reflects them?

Sam Coombes, an actor and steelworker of ten years, on set of the play We’re Still Here

(Photo Credit: Demitris-Legakis)

On set Sam Coombes paces, going over his lines. He has only ever been in pantomimes put on by his local rugby club, and this is his first professional gig. But he isn’t behind a velvet curtain clutching a skull, and there are no exclamations of “Alas, poor Yorick!” here.

It’s September, and an empty warehouse on the site of the old Byass tin works has been transformed to resemble steelworks. Sam’s costume of blue overalls is almost identical to what he wears daily—he’s a steelworker, 29, from Taibach. “It really felt like I was in work,” he laughs, when recalling the set. “Damp, cold, smelly, dirty, with a healthy population of rats!”

The play was We’re Still Here, a production by the Common Wealth Theatre and National Theatre Wales. Performed in Newport, it told the story of the Save Our Steel Campaign of 2015-16.

Working class culture, voices, identities, lives: all were celebrated in the production.

In South Wales and beyond, working class people are not only sharing their experiences of the arts, but are increasingly able to shape that world into something more familiar thanks to companies like Common Wealth Theatre. The company aims to show that ordinariness is beautiful and to elevate working class culture into the realm of art.

But this can only happen if working class people are able to get involved.

Platforms slowly emerge

Rhiannon White, 33, hails from St. Mellons, a large council estate, and co-founded Common Wealth Theatre. The company unofficially started in 2008 when the current team had just left university and were squatting in “large, empty buildings,” penniless and creating theatre for “people who don’t usually think it is for them.”

They were fearless, Rhiannon says, and the Cardiff and Bradford based company was formally launched in 2011. Our Glass House went on to win the Special Commendation Award at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2013.

She has recently published a report which is the culmination of research into working class participation and representation in the arts.

Class: The Elephant in the Room not only focuses on getting into the arts, but the way we need to address what comes to mind when we think of “the arts.”

Recent statistics cited by Labour’s Acting Up report showed that only 16% of actors come from working-class backgrounds compared to 51% from privileged backgrounds.

Rhiannon hopes work like hers, which brings people’s experiences to the fore, can widen the debate. A lot of great work is being created in Wales, she says, but the problem runs deeper. “It’s about how art is managed and about how impenetrable the industry is,” she adds, “The hierarchy very much exists.”

Because working class people have been excluded from the arts, the work produced has therefore failed to represent their experiences.

The creative director of Common Wealth Theatre hopes theatre is slowly becoming more inclusive, but the journey is not easy for those trying to get ahead.

Discrimination and disheartenment

Even in the tin works, on the set of a professionally produced play of which he was the lead, in a place purposefully chosen to mirror his life’s spaces, Sam sometimes felt like an outsider.

In between rehearsals he was approached by a Radio 4 reporter who, he says, “came up to me and point blank said ‘What are you doing here?’ He hadn’t realised Sam was in the play but thought that he was lost. The reporter, realising, went on to say: “You don’t look the type to be in something like this.”

In that moment, Sam realised that “someone like me wasn’t usual.”

Gareth Chambers has experienced alienation in his career, too. He is a dramaturg, actor and director in Cardiff who feels that being a working class gay man has caused him to be denied opportunities throughout his career.

Gareth uses a lot of what he calls “low art” in his work to counteract “the stuffy and snobby” perception he thinks people have of dance. (Photo credit: Gareth Chambers)

He says: “Nepotism is rife in Cardiff. It’s painful and it can cause a lot of trauma. I recently applied for a major award from a funding organisation. After having a good chance of getting it, I didn’t.”

The ability to write an application for funding, the confidence to articulate an artistic vision, the fear of rejection: these are things many of the people Rhiannon interviewed for her report felt held them back.

He is thankful to Common Wealth Theatre for giving “power and agency” back to people like him.

Changing people’s perceptions of art is a big ask, but inclusivity and representation are words Rhiannon now hears more often paired with “the arts.” “Something is starting to happen,” she tells AltCardiff. “Even on a national level the conversation has started.” Beauty is no longer one size fits all. The work of her hundreds of interviewees, Rhiannon says, is “raw, it’s beautiful and it’s theirs.” Rats, damp and cold included.

Other voices in Wales speak about socially inclusive theatre:

“When National Theatre Wales was set up we made ‘community’ a core value i.e. it’s part of everyone’s role. It means we can build long term relationships over time and have worked with a range of communities and people, many of whom may fall into the category of ‘hard to reach’.”

- Devinda De Silva, Head of collaboration, National Theatre Wales

People often perceive theatre as grandiose, but theatre companies are trying to change that (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

“The council is committed to theatre and the arts in the city and especially that its cultural offer is accessible and of relevance to all of its citizens. The Council’s Cultural Projects Scheme (CPS) has supported a number of small community arts projects. These projects provide match funding to grassroots arts activity that has a transformational impact on participants’ lives.”

- Councillor Peter Bradbury, Cardiff Council, Cabinet Member for Culture and Leisure

We’re Still Here by Commonwealth Theatre challenged perceptions of what theatre looked like (Photo credit: Jon Poutney)

“I see more and more small theatre companies trying to put on innovative work which I think is great. However mainstream theatre to me does still very much cater for the few. By going into schools, we hope to use the creative arts in order to include those who are usually excluded from the theatre scene, and in this way challenge perceptions of theatre and what art can be.”

- Michael Barnes, Educator and Actor at Going Public Theatre, a charity formed in 1990 that focuses on theatre in education

Cardiff-based Eno Theatre recently showcased “Writing to Reach You,” a performance about mental health (photo credit: Nerida Rose Bradley)

“Theatre is usually grandiose, white buildings inaccessible to most people. A big problem with theatre in Cardiff at the minute is that it’s very very very white. There’s a huge problem with BME talent not being recognised within Wales.”

- Danny Muir, Freelance Producer, Eno Theatre