General Election 2017: The TV Debates

As election fever ‘grips’ Wales, speculation over whether or not Prime Minister Theresa May will eventually agree to take part in any televised Party leaders debates continues. Since the election was called on April 18th, Number 10 sources have firmly ruled out the possibility. On that day, May’s spokespeople told the Guardian that there was simply no need for the PM to be challenged by Jeremy Corbyn and others. And, from her position of strength in the opinion polls, May’s position is understandable. The received wisdom is that TV debates don’t favour incumbents. The performances of lesser known politicians (see Nicola Sturgeon in General Election 2015 and Nick Clegg in 2010) suggests that viewers are likely to look more favourably upon those who don’t hold the highest office.

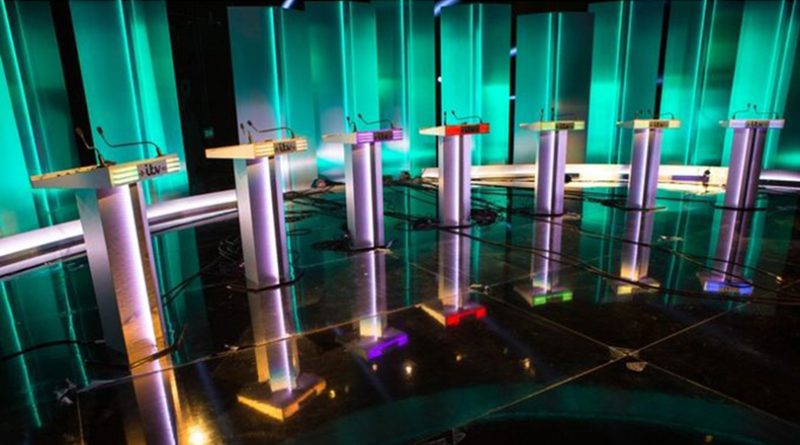

But last week ITV announced that it would go ahead with a leaders debate without May or Jeremy Corbyn, who has indicated that should the Prime Minister not appear, neither will he.

Even an hour is a long time in modern politics though and given that May’s campaign is progressing with such distinct unease (though admittedly without affecting poll standings) we might well see a U turn of Cameronian proportions. She began promisingly enough with a commitment to “actually get out and about and meet the voters” but recent Brexit difficulties, a clear determination to not actually meet any voters at all and the wish to restrict media coverage of her movements by locking reporters away has meant that the Prime Minister looks more like the Prime Sinister. Unapproachable and distant, perhaps a TV debate would ignite her campaign and breathe life into an election which overall has thus far failed to engage.

If recent surveys are to be believed there is certainly public appetite for debates. In the 2015 election a YouGov poll showed that 69% of respondents thought they should be held with 57% saying they were good for democracy.

Add to this the fact that seven million people tuned into to ITV to watch the leaders of the seven major parties debate and we have a modern political phenomenon. Research group Panelbase also found, in a survey of over 3,000 people, that of those influenced by TV, 61% were influenced by live political debates, 38% by national news and only 16% by party political broadcasts. Under these circumstances it would seem to be a mistake for May to decline to appear. Her nonattendance would only add to the image of a disconnected leader – particularly if, as has been suggested, her absence would be signified by the presence of an empty chair.

The TV debates, in the UK at least, are a relatively new development. In 2010, Gordon Brown, Nick Clegg and David Cameron appeared in three 90 minute programmes on ITV, Sky and the BBC respectively. They were in many ways exhausting events and the real surprise was not so much the emergence of Clegg as a serious debater but that the idea had taken so long to come to fruition.

In 1964 Labour’s Harold Wilson challenged Tory PM Alec Douglas – Home to what is now called a ‘face off’. Wilson was then the new breed of politician embracing the ‘white heat’ of technology, determined to reform the political landscape. He saw himself very much in the mould of John F Kennedy and there is no doubt that Wilson was influenced by the Kennedy – Nixon presidential debates of 1960, the first to occur on US television.

The first of these unquestionably changed western political communication as the younger, more handsome and debonair Democrat JFK stood opposite the ‘sickly and sweaty’ Republican Richard Nixon. Popular history tells us that those that who listened to the debate on radio had Nixon victorious whilst the majority of the population (TV audiences have been estimated as high as 74 million) who watched on TV had Kennedy as the clear winner. The Republicans were so disconcerted by the whole experience that TV debates did not occur again until 1976, some sixteen years later. But the point is that how a politician looked and presented themselves visually was gaining currency.

In the years that followed in the UK it was mainly the sitting leaders who consistently refused to be drawn to debate. Or to be more accurate, party leaders ahead in the polls preferred not to take the risk. In 2001, Tony Blair was in such a position of strength that Lance Price, his special advisor, revealed that:

“We were never up for it. We were way out ahead in the polls. It wasn’t a question of whether or not we would agree; it was a question of when and by what means we would get out of it.”

Gordon Brown had no such security in 2010 and the UK public had its’ first taste of this quintessentially American procedure – with a particularly British taint. Questions were posed by a selected audience who were forbidden from clapping or indeed registering any sort of response. Under a 76 page format agreement there were no questions specifically for the leaders (they addressed common themes) and they were able to appeal instantly if they perceived a lack of balance in questioning.

Since then, as I’ve written, the format has been well received. Peter Bazalgette, Former Chairman of Endemol UK (the company responsible for Big Brother and Deal or No Deal) has lauded the power of TV debates as mass audience events, likening them to talent shows where the thrill is in the live competition.

They are also refreshing in the sense that they signify a purer politics unencumbered by the razzamatazz of campaigns dominated by platitudes, advertising and the historic attrition between politician and broadcaster.

So the ITV debate on May 18th is to be welcomed – even if their attraction to viewers will be severely limited by the absence of the two main party leaders.