Evolution not revolution: news in the digital age

Posted by Professor Justin Lewis

Amidst the wealth of data to come from the latest Ofcom research on news consumption we find a mixture of continuity and change. Since change is more newsworthy than continuity, the figures on the newer, online sources of news will get most attention. It is probably the emergence of Facebook, Google and Twitter as online news sources will capture the blinking eyes of the Twitterati.

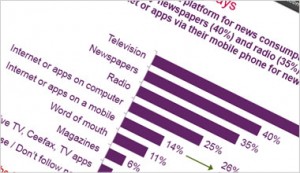

Yet Ofcom’s data is a reminder that those activities that occupy the twittering classes sometimes have only a limited appeal. The traditional sources of news remain the big beasts of the news landscape: 78% get still their news from TV, 40% from newspapers and 35% from radio. While the proliferation of audio-visual devices now clutter the cultural environment, television retains its place at its centre.

In earlier surveys, it looked as if the internet would rapidly overtake radio as a source of news, but it remains behind – if still close – on 32% . A significant presence, certainly, but less ubiquitous than we might have predicted 10 years ago.

Indeed, it appears that in an age characterised by a plethora of information sources we are increasingly likely to turn to our foremost public service broadcaster. When people are asked to name their top three sources of news, three of the top four are BBC outlets: BBC 1 (57%), the BBC News Channel (17%) and the BBC website (16%). Since 2010, the BBC is the only TV news broadcaster to have consistently increased its share of the TV news audience.

For the last 50 years, the BBC’s main rival remains as a news source has been ITV, and although ITV’s share of the TV news audience has declined, ITV retains its position – by some distance – as the second most used news source.

Many commercial news operations will grumble about what they see as the BBC’s unfair advantage, allowing it to dominate across TV, radio and online. But its popular appeal as a news source may be precisely because of its clear public service remit. With so many sources of information available, a reputation for quality, trustworthy journalism becomes ever more valuable.

This places a burden on the BBC, whose commitment to accuracy, impartiality and quality journalism requires constant, careful and independent review. The BBC is well placed to shoulder this responsibility: it is, after all, there to serve the public who own it rather than a narrower set of private interests.

But what about young people? It has become a contemporary cliché to say that ‘young people get all their news online these days’. The data suggest that there is only a margin of truth in this. The 16-24 age group still prefer TV news to online, but their use of the internet for news is hardly rapacious – roughly the same as it is 35-44 year olds. Use of online sources drop markedly for age groups over 55, but the dividing line here is middle age rather than youth.

The 16-24 age group may be less likely to use traditional sources of news, but this disinterest is not compensated by a turn to online. Young people are the group most likely to rely on ‘word of mouth’ (16%) or consume no news at all (14%).

If we look at the use of online news sources, we also find continuity and change. The digital divide remains firmly in place, with social class being a more important barrier to the use of online news than age. Half of those in social classes A and B use online news sources, compared to less that one in five in social classes D and E.

The website with by far and away the most reach – with 52% of internet users turning to it as a sources of news – is the BBC. But in second place – ahead of Sky, ITV, or any online newspaper – is Facebook (19%). Google news (13%) and Yahoo news (10%) also do well – indeed as many people go to Yahoo for news as Twitter.

The significance of Twitter as a news source is amplified by its popularity amongst journalists and people in the public eye, but this has also meant it has probably received more attention than its general popularity (or lack thereof) merits. If we’re interested in where people get their information from, we should be paying as much heed to the rise of search engines as news providers.

Their success – like many other aspects of consumer culture – is matter of convenience. Google and Yahoo do well because they’ve already got our attention. For the much the same reason, Ofcom’s data show that as many people get their news from BBC Radio 2 as from Radio 4 or the Daily Mail (all on 8%). News may be a counterpoint to advertising, but it has a similarly ambient presence in many media forms.

It’s worth pondering on this. For journalists, politicians and academics, successful newspapers like Daily Mail or the BBC flagship Radio 4 news programmes like Today occupy a significant place in the news firmament in a way that Radio 2 or Yahoo does not. Ofcom’s data suggests we begin to take these more ambient forms of news more seriously.

The success of traditional newspapers in establishing an online presence is decidedly mixed. While the print version of the Times outsells the Guardian by a distance, when we include online readers the position is reversed, with the Guardian clocking up nearly a million more readers overall. Of the other newspapers, only the Mail and, on a more modest scale the Independent, have significantly increased their readership by combining online with print.

There are many more stories told by Ofcom’s research. But for now, the picture it presents is not a transformation, but a news world gradually evolving to incorporate digital technology.