How to beat aggressive government propaganda in the Boris Johnson age

Posted by Dr David Dunkley Gyimah

This post originally appeared on the schools “Emerging Journalism’ site on Medium – The Scrum

He cut an unlikely image for someone with the reins of power in his grasp walking through his apartment with a phone war-gaming his next move. Rotund and suited, first would be the deliverance of his upbeat message to the masses counterpointed by the menace of socialism.

Secondly, he needed to realign the crisis’s narrative into quite a different believable one that a gullible public could absorb. Thirdly, getting the press on his side; they would be the critical instrument for his deception. A fake news outlet he set up would contribute articles for the newspapers as he cosied up to national editors who shared his values.

His coup de grace was the belief that only a “trifling faction” were capable of understanding how he could bend reality and do anything about it, “who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses”. The public who were the real object of his focus were too irrational and stupid to see through his actions. Actions, he viewed as true democracy. It was for their own good.

Control the narrative. Let the media and newspapers take up the fear and spread it to the populace. This in turn would prompt a groundswell of discontent and new voting intentions. Huddling politicians would then top this off by creating misplaced laws to protect a fake threat. This was how corporate establishment would control power

Control

If it sounds familiar for our times, that’s just the half of it. Brexit is about taking back control so Britain can regain its empire status. National newspapers are the witting uncritical organs of disseminating this narrative. The damage? Nothing new here in a digi world where a person’s data points are being hoovered up and ads bombard people in a concerted effort of propaganda.

This, however, is the 1950s as Edward Bernays masterfully corrupted the gift from his Uncle Sigmund Freud to help topple a government in South America; just one of several campaigns. That gift was psychoanalysis.

Bernays, commonly characterised as the father of public relations invented the playbook. A natural at self publicity, through his uncle he realised, how unlike Freud, manipulating the unconscious mind was the key to making millions of dollars.

He worked the interests of a commercial company in Guatemala United Fruit Company (that sold bananas) to topple a democratically elected socialist-democrat government, led by Jacobo Arbenz Guzman. Bernays scared its neighbour the USA enough into believing that the government was being managed by the Communists from the Soviet Union.

It wasn’t. But the mendacious work this evil genius promulgated, with input from an unwitting press, (and the CIA ) would become the blueprint for many political enterprises and PR professionals to tap into the unconscious and uncontrollable desires of people. The pivot was the efficacy of democracy, which as Adam Smith put it, “All for ourselves and none for the people”. A democracy in which “men of best quality” must rule over the “rascal multitude”.

Arbenz was elected on a popular mandate by the people and sought Agrarian reforms by seeking to purchase unused land for farmers from United Fruit at $3. United Fruit costed its land at $75 a piece. This difference would dent their profits and monopoly; they were making $54m a year.

Bernay steered the story away from the commercial company’s profit sheet into one about the threat of communism. His fake news outfit the Middle America Information Bureau sent out press release after press release to the US national press and even flew some editors to Guatemala to show them an alternative reality.

Journalism was no match for Bernays’ methods and is no match today. Yes, Bernstein and Woodward put Nixon’s feet to the candle, but largely corporate and government propaganda slayed their lanes. Still works. And will most likely work 200 years from now. Two loose facts about Bernays; he disliked experts. Where have we since heard that. Goebbels was a fan and would use his methods.

What then is the function of journalism and a healthy democracy when it either finds itself abetting corporate propaganda, or fails abysmally to protect democratic citizens from sophisticated techniques of mass manipulation?

The truth can be warped by proclaiming an alternative repetitively. False flags and dog whistles can effectively be created by aligning them with our unconscious fears. And what appears in a newspaper has the power to shape thought and mood in validating prejudices or even creating them, even when risks associated with the story are conspicuously non-existent. Forget the media’s debatable hypodermic theory. Bernays knew that. Award winning psychologists Daniel Kahneman captured it his book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

What now?

In an era of meta hyperdigital, of targeted news, of the populace’s penchant for tech over substance, and the reliance on social media as the purveyor of truth, now more than ever the threat to humanity in the most naked information wars ever sees large areas of the press and journalism as integral parts of the problem. Journalism might fulfill other functions within entertainment, the weather, etc. but in political discourse?

A lot of what journalism perceives as its duty is the rational intelligent construct of words and text on a page to make sense of events that to the best part sate the middle-road consumer’s appetite. It asks what the story is, engages in editorial debates around angles, entombs itself in a plethora of journalistic ideologies and sends out its reporters.

But if the events of recent years haven’t shown us, then Bernays swinging from his uptown apartment’s chandeliers prophesied journalism is broken. What when the audience is irrational, or politicians ride roughshod with their dogma? Some journalists, I’ve written about, are finding holes.

Tertiary institutions offering journalism curriculum for the next generation will attempt to undergird lectures with various media theory such as semiotics, or a series of edicts some long contested in The Elements of Journalism.

What journalism should be doing is engaging in wholesale re-education, shifting to mental aptitude: psychoanalysis, behavioral, nudge theory, and the neuroscience behind stories? Note when a UK lecturer wanted to combine journalism with PR she attracted a fair bit of flak. Yes, they’re not the same but understanding how PR professionals think is the least you should know.

Washington Posts journalist Greg Sargent spells out a deep crisis of politics and the press with 45, which goes beyond the artifices of previous politicking.

What’s notable is the sheer comprehensiveness of the effort to create an alternate set of realities whose departure from the known facts seemingly aims to be absolute and unbridgeable.

Newsrooms engage in story strategy. Some academics like Jay Rosen, acutely aware of the disinformation war, have laid out their ideas to tackle falsehoods from the White House. The president knows the media must cover him. That means he has carte blanche to double down on claims and then attempt to rewrite afterwards — reconstitute narratives. What can the press or senators do? There’s no immediate penalty for falsehoods and after that news cycle viewers move on.

Some of Jay’s ideas include boycotting 45’s coverage, particularly live events where spin goes largely unchallenged. Covering the president as a subordinate to the story, rather than he being the main character; and making informed decisions about squirrels and dead cats.

In the UK, we see a similar strategy in play with the new Boris Johnson government in which BBC Radio 4 host Mishall Husain in the clip below expresses surprise when the foreign secretary Dominic Raab insists no deal has been a consistent theme of his. There’s no sanction for falsehoods. The irrational public is the target.

Television is overly susceptible to the foils of PR because of inherent legacies of production from the 1950s. At press conferences invariably television cameras sit at the back, whilst photojournalists place themselves at the front. This may seem convention, as 45 takes repeated pot shots, but then convention are cues and standards adopted at a particular time and place.

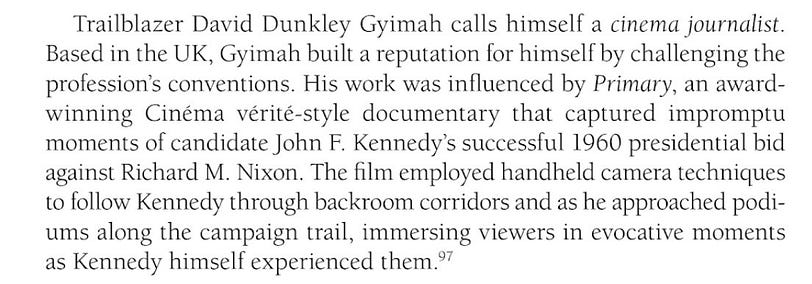

When photojournalism editor Robert Drew turned his hand to television journalism in the 1960s he upended a series of conventions. One major breakthrough was the adoption of cinematic tropes and the mobility of newly designed cameras. Drew would be called the father of Direct Cinema. For a while his methods caught politicians off guard. Ultimately, as Drew points out in this interview with me, television news took his equipment, but discarded his techniques.

A decade ago, completing a PhD, I revived Drew’s thinking expanding further on the notion of cinema and the art of newsmaking in which the journalist made conscious choices in style and substance across the spectrum of cinema langue. How could they prevent themselves being led by the nose in the news agenda?

Journalist and professor Ed Madison and Ben DeJarnette captured a flavour of it in 2018 in Reimagining Journalism in a Post-Truth World where they saw the connection.

Research across four continents and some of the world’s leading journalists unearthed several award-winning videojournalists using cinema to tell stories. The term reflects the psychology, tropes and styles behind storytelling. If advertising is devoted to creation of artificial wants, writes Chomsky in Taking the Risks out of Democracy, then cinema journalism is devoted to understanding those wants in the way its protagonists tell their stories.

Like Drew, it’s traction first amongst journalists was viewed with suspicion. In 2007 whilst teaching the first newspaper journalists in the UK its form, several wondered how their editors would take to seeing Bela Tarr’s Werkmeister Harmonies style in news, but since then many have come around.

Cinema journalism or otherwise, it’s become clear that journalism practitioners and educators require new set of skills to win the battle of the message against the onslaught of psychedelics’ practices. To do the job right, said Bernays, the PR practitioner needs to be “smart and intuitive”, he needs “to understand psychology and sociology to get underneath the skin of the public and the client”. He continues:

His methods were to define your objectives; conduct research; modify your objectives based on your research; set a strategy; establish themes, symbols and appeals; …decide on the timing and tactics; and carry out your plans.

Sounds like something out of a thesis, or even a start up business, but it’s over 50-years old and still used to kaibosh journalism.

Time for a wake up call.